Stem cell-derived neurons from combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) react differently to a stress hormone than those from veterans without PTSD, a finding that could provide insights into how genetics can make someone more susceptible to developing PTSD following trauma exposure.

The study, published October 20 in Nature Neuroscience, is the first to use induced pluripotent stem cell models to study PTSD. It was conducted by a team of scientists from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center, the Yale School of Medicine and The New York Stem Cell Foundation Research Institute (NYSCF).

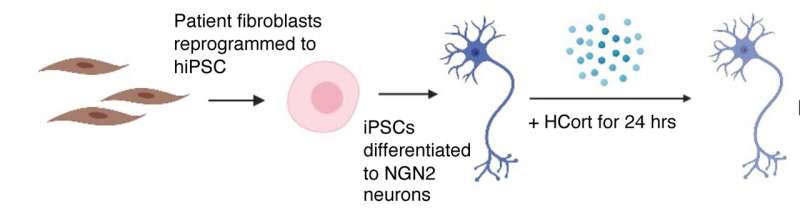

Post-traumatic stress disorder can develop following severe trauma and is an enormous public health problem for both veterans and civilians. However, the extent to which genetic and environmental factors contribute to individual clinical outcomes remains unknown. To bridge this information gap, the research team studied a cohort of 39 combat veterans with and without PTSD who were recruited from the James J Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the Bronx. Veterans underwent skin biopsies and their skin cells were reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells.

“Reprogramming cells into induced pluripotent stem cells is like virtually taking cells back in time to when they were embryonic and had the ability to generate all the cells of the body,” said Rachel Yehuda, Ph.D., Professor of Psychiatry, and Neuroscience, at Icahn Mount Sinai, Director of Mental Health for the James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and senior author of the paper. “These cells can then be differentiated into neurons with the same properties as that person’s brain cells had before trauma occurred to change the way they function. The gene expression networks from these neurons reflect early gene activity resulting from genetic and very early developmental contributions, so they are a reflection of the ‘pre-combat’ or ‘pre-trauma’ gene expression state.”

“Two people can experience the same trauma, but they won’t necessarily both develop PTSD,” explained Kristen Brennand, Ph.D., Elizabeth Mears and House Jameson Professor of Psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine and a NYSCF—Robertson Stem Cell Investigator Alumna, who co-led the study. “This type of modeling in brain cells from people with and without PTSD helps explain how genetics can make someone more susceptible to PTSD.”

To mimic the stress response that triggers PTSD, the scientists exposed the induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons to the stress hormone hydrocortisone, a synthetic version of the body’s own cortisol that is used as part of the “fight-or-flight” response.

“The addition of stress hormones to these cells simulates biological effects of combat, which allows us to determine how different gene networks mobilize in response to stress exposure in brain cells,” explained Dr. Yehuda.

Using gene expression profiling and imaging, the scientists found that neurons from individuals with PTSD were hypersensitive to this pharmacological trigger. The scientists also were able to identify the specific gene networks that responded differently following exposure to the stress hormones.

Inside the cells of PTSD-affected individuals

Most similar studies of PTSD to date have used blood samples from patients, but since PTSD is rooted in the brain, scientists need a way to capture how the neurons of individuals prone to the disorder are affected by stress. Therefore, the team opted to use stem cells, as they are uniquely equipped to provide a patient-specific, non-invasive window into the brain.

“You can’t easily reach into a living person’s brain and pull out cells, so stem cells are our best way to examine how neurons are behaving in a patient,” said Dr. Brennand.

NYSCF scientists used their scalable, automated, robotic system—The NYSCF Global Stem Cell Array—to create stem cells and then glutamatergic neurons from patients with PTSD. Glutamatergic neurons help the brain send excitatory signals and have previously been implicated in PTSD.

“As this was the first study using stem cell models of PTSD, it was important to study a large number of individuals,” said Daniel Paull, Ph.D., NYSCF Senior Vice President, Discovery & Platform Development, who co-led the study. “At the scale of this study, automation is essential. With the Array, we can make standardized cells that allow for meaningful comparisons between numerous individuals, pointing to key differences that could be critical for discovering new treatments.”

Leveraging the hallmarks of stressed PTSD cells for new treatments

The team’s gene expression analysis revealed a set of genes that were particularly active in PTSD-prone neurons following their exposure to stress hormones.

“Importantly, the gene signature we found in the neurons was also apparent in brain samples from deceased individuals with PTSD, which tells us that stem cell models are providing a pretty accurate reflection of what happens in the brains of living patients,” noted Dr. Paull.

Moreover, the distinctions between how PTSD and non-PTSD cells responded to stress could be informative in predicting which individuals are at higher risk for PTSD.

“What’s really exciting about our findings is the opportunities they offer for accelerating the diagnosis and treatment of PTSD,” Dr. Paull continued. “Importantly, having a robust stem cell model provides an ideal avenue to drug screening ‘in the dish,” even across diverse patient populations.”

“We’re working on finding already-approved drugs that could reverse the hypersensitivity we’re seeing in neurons,” added Dr. Brennand. “That way, any drugs we discover will have the fastest possible path to helping patients.”

The researchers plan to continue leveraging their induced pluripotent stem cell models to further investigate the genetic risk factors pinpointed by this study and to study how PTSD affects other types of brain cells, helping to broaden opportunities for therapeutic discovery.

Source: Read Full Article