When I was five, my parents divorced. Shortly after, my father met Sandy, first at a cocktail party and then again at a tennis league for single 30-somethings around Portland, Maine. She was brilliant, anxious, fast-talking, and from old Chicago money. They were engaged within two years.

Sandy was a perfectionist and held us, her family, to the same standards. She placed yellow Post-it to-do lists around the house, sent my new stepbrother and me to etiquette classes (our dog wasn’t spared, either), and could cut me to shreds with a single remark and gesture to my father: “He’s wearing that?”

I understand now that if Sandy was hard on us, she was even harder on herself. But when my mother dropped me off for the weekend, I’d hide out in the garage to avoid facing her. At dinner, I’d fix my eyes on the floor. I saw my father’s growing affection for my stepbrother and wondered, “What the hell is wrong with me?”

We all have stories in our histories we’re holding on to—tragic plotlines that seem to run through everything we do. I’ll never find true love. I’ll never be a success. I’ll never get past what happened to me. The more we believe them, the more our prophecies seem to self-fulfill.

And let’s be clear: My initial childhood trauma wasn’t all that tragic. There’s a generic mildness to it that survivors of all kinds of harsher abuse or tragedy might resent. But the story that Sandy had seen some fatal flaw in me ran deep. I believed I was inherently bad and inferior, that nothing about me was okay. Author and self-help guru John Bradshaw calls this condition “toxic shame,” the feeling that no matter what we do, we’re wrong. And it doesn’t take a five-alarm altercation or hellacious abuse for it to start festering.

The price of unverified “truths”

To cover up, I went out into the world trying to be perfect. If I impressed everyone I came into contact with, maybe I’d feel okay. The powerful, important, rich, and influential came into my crosshairs. They represented Sandy for me, and winning these types of people over became an obsession. In college, I dated a fabulously wealthy young woman and tried to integrate into her milieu of private jets and lavish vacations. Years later, in New York, I set my sights on the world of high fashion as a magazine writer. I thought rising to the highest ranks would prove to everyone—myself most of all—that I was worthy of being alive.

It didn’t work. No matter how many times my face or my byline appeared in print, no matter how beautiful the women I dated or how impressive my Instagram feed, I felt unfulfilled. I even tried spirituality as a remedy for feeling inferior, but there’s not enough meditation in the world to fix an old story that says, “I’m a piece of shit.”

Illustration by Alex Arizmendi

Meanwhile, the anger and confusion I carried about Sandy came out in strange ways. For instance, any woman in my life who became angry with me or who held a position of authority—girlfriends, bosses, editors—I took a special interest in torturing. I turned my back on them, burned them, left them hanging. It was like I was getting back at Sandy through them.

Uncovering the real story

Sandy and my father divorced in 2005. He embezzled money from her, and she caught him. Not long after, he committed suicide. In the following years, I shut the door on Sandy. Her e-greeting cards on my birthday most years went unanswered. I tried to forget she existed. But in 2016, while digging through some old files, I uncovered the program from my father’s memorial service. I read the speech Sandy had given that day and felt myself go rigid at the final lines:

“But most of all, Sean, he loved you, his son. And that is the message and image I so very much need for you to hear right now.”

I felt the pain of loss well up in my chest. I remembered that afternoon at the service, sitting there, still unable to make eye contact with Sandy as tears streamed down my face. I told my therapist, Jacob, about the memory. “Maybe you should go see her,” he said. The thought of talking to Sandy face-to-face terrified me, but Jacob explained to me that the scariest place I didn’t want to go was where the wisdom was. That’s what sets you free. And I wanted to be free.

The only way out was through

That spring, I reluctantly began a series of meetings with Sandy in Maine that would span three years. The first, a four-hour lunch at her country club, was simply a reintroduction. Sandy sat across from me tanned and freckled, the deep creases on her face showing her age. She spoke anxiously, smiled often, and even got a little teary when we said goodbye. The meeting seemed to touch her. I asked my mother on the phone later that afternoon: “Is it possible that as an adult I actually like Sandy?”

During our second meeting, Sandy trusted me with sensitive information about my father’s deceit and their resulting divorce. And at our third, we again spoke for hours, sharing stories. She even apologized, telling me: “If I was ever hard on you, I regret it.” With each of our meetings, I realized that all the work I’d done in therapy and on my recovery was freeing me from the expectations I’d had for Sandy that had been clouding my perception. I could see her more clearly now. She wasn’t scary. In fact, with each meeting, I saw more of her pain, more of her humanity.

It’s been my experience as a life coach that behind whatever kind of childhood trauma we’ve been through—sexual, physical, or emotional abuse, addiction, divorce, suicide, being cut from a sports team—is a core story we have about ourselves. Common ones include: I’ll never be enough. I don’t deserve love. I’m better off dead. As long as these stories exist, we find ways to perpetuate them.

There’s a funny thing about these stories, though. They tend to crumble under examination. This can be done in many ways, including with a therapist, life coach, support group, or twelve-step sponsor. It can also be done by going back and facing the very thing we fear.

I painted Sandy as the enemy for most of my life, which kept me angrily trying to prove her wrong, and it nearly buried me.

But thanks to my therapist’s suggestion and my willingness to follow through, the story I’d been carrying around all these years was being proven untrue. Sandy clearly didn’t hate me. And if that wasn’t true, maybe I wasn’t terrible. Maybe I’d never had anything to prove.

Sunlight vs. the story

As I stopped feeling like I had to impress everyone, I became less angry. I started treating myself better. The critical voice inside my head that I’d always identified

with Sandy began to fade, replaced by a gentler message. I’m okay. In fact, I got so okay that I started thinking about how I could help others. So when I went home to Maine last October, I decided that instead of continuing to hold it over Sandy’s head that she’d never cared about me, I’d do something revolutionary: I’d show up ready to care about her.

.

Subscribe Now

hearstmags.com

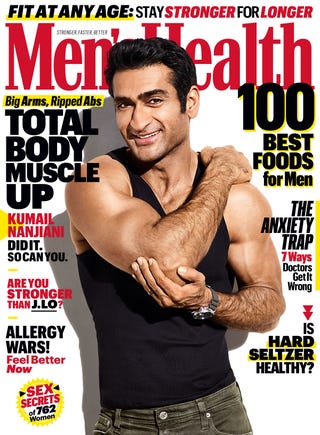

Subscribe to Men’s Health

My stepbrother was back home with his new fiancée, and we all gathered at Sandy’s house for dinner. We sat at the old dining-room table where we’d eaten dinner hundreds of times during my childhood. I could see Sandy was anxious, that she wanted to make me feel welcome, so I tried to set her at ease. “It’s good to be here,” I told her. Later that night, I sent her an email: “I was angry with you for many years,” it said, “but I’m not angry with you anymore. You’re the only stepmother I’ll ever have, and it’s important to me to have a relationship with you.”

The next morning, walking along the ocean in my hometown, I had a vision of the four of us—my father, Sandy, my stepbrother, and me—all in my dad’s old truck, laughing wildly. It was the first time I could remember having such a happy memory from my childhood, and I knew that it meant I was free. I’d finally let go of the old story.

Old stories will always replay until we examine them, but out beyond the stories we tell ourselves is opportunity. When we have the courage to challenge and drop an old narrative, it’s often rewritten better than we could have imagined.

Letting go of the story that Sandy would never be the stepmother I needed because there was something wrong with me allowed her to become something I actually wanted: someone who can support me on this tougher-than-I-ever-imagined road of being human. And that’s all I can ask for.

Source: Read Full Article