Women’s safety in public space is very complex. Women’s perception of safety—as opposed to their risk of experiencing gendered violence or crime—very much determines how they interact with public space. This issue of perception makes measuring and evaluating women’s experiences difficult.

The passing of the Gender Equality Act 2020 in February 2020 created a legal imperative in Victoria to shift urban politics, policies, design and research towards understanding how gender affects needs and experiences. This is generally poorly understood by those who determine how places are designed, developed, governed and maintained.

Tackling the inclusion of women in all aspects of public spaces will be paramount, but it cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Nuanced thinking and multiple gender-sensitive strategies are required.

In local streets, parks, squares and walkways across Australia we saw a marked increase in the numbers of people walking and cycling under COVID-19 restrictions that allowed people to leave their homes for exercise. Coupled with the big drop in car traffic, these public spaces may have felt like they had never been safer.

But are these spaces safer for women? And how will we measure women’s perceptions of safety in a (post-)COVID world?

What makes women feel safe or unsafe?

For women, safety considerations not only involve the physical aspects of spaces, but also how memories and mental images are triggered. For instance, the many high-profile cases of women who have been viciously attacked, raped and murdered mean many women are on alert every time they leave home. Daily sexual harassment maintains those high levels of fear because it reminds women of their vulnerability to sexual violence.

Research has shown experiences of public space are individual and unique. Women from different racial backgrounds and of different ages, sexuality, disabilities and socio-economic class have very different experiences. Indeed, one woman’s experience of a place as “bad” might be contradicted by another’s account of the same location.

This means we must also consider how women’s differing and intersecting identities shape their individual and collective experiences—and thus perceptions of safety in public space.

Understanding these complex experiences for women in greater depth means gathering more gender-specific data. Right now, we have far too little data about women’s experiences and knowledge. Or, rather, the information is in a format that is too general and too easily dismissed.

Every place is a little different. The women who use those spaces are different too. We need data that target precise areas.

Women’s safety audits on the rise

One key method of gathering such data is women’s safety audits. The Metropolitan Toronto Action Committee on Violence Against Women and Children developed the first of these audits in the late 1980s. This approach has since been adopted and adapted to suit local conditions and changing technologies.

At the heart of these audits is users of a public space noting the factors that make them feel unsafe or safe, and identifying ways to make the space better and safer. It is a process of co-design—women are viewed as experts in their lived experience.

Typically, an audit will consider different kinds of spaces—such as streets, residential areas, parks, markets and public transport—and offer a checklist of matters to consider. Part of any audit are issues like lighting, surveillance and sightlines.

Women are also asked to consider matters such as how many women are in the space and what they are doing. Are they taking their time? Are there reasons and opportunities for women to gather in the space?

Simply, are women inhabiting the public space, not just quickly passing through it, keys in hand as a ready weapon? This makes a big difference to perceptions of safety and to the sense that women actually belong and are entitled to take up space in public.

What’s being done locally?

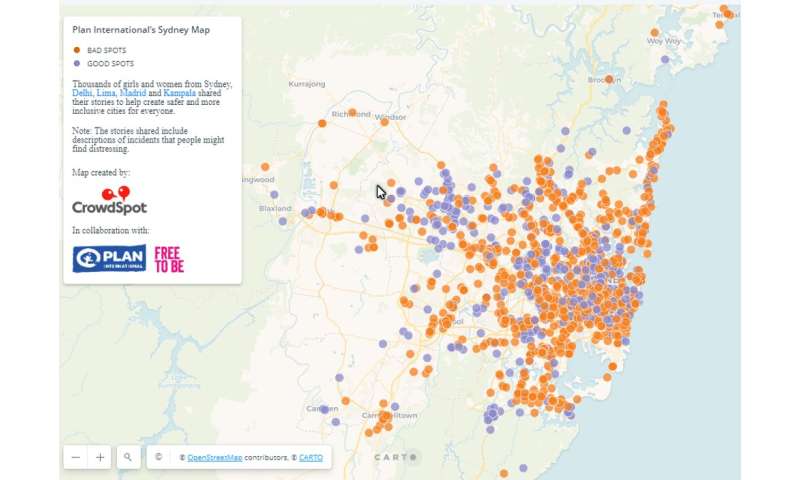

Audits now come in different forms. Digital crowdmapping platforms, such as Safetipin and Free to Be, allow women to use geolocation software to pinpoint precisely where they feel safe and unsafe, and why. Safetipin now generates safety scores for very localised parts of the cities where it is active.

Online survey audits and tailored checklists are also becoming increasingly useful for local governments as they tackle merging traditional crime prevention through environmental design strategies with a gender lens.

With the Gender Equality Act in place, many local governments are leading the way. As a part of its Family Violence Prevention Strategy, the City of Casey has been working with Monash University XYX Lab to develop the “Safe in Her City” gender audit tool. Another XYX Lab partnership with Moreland City Council is an online safety survey to shed light on women’s experiences of a short stretch of Merri Creek.

Both these initiatives build upon global good practice by applying a gender lens and incorporating the voices of women and girls into city design and evaluation. In this way, cities can promote safety and belonging in their public places and spaces.

Navigating the ‘new normal’

While instances of gender-based violence rose frighteningly in private and domestic realms during COVID-19 lockdowns, it is equally important to track what is happening now—in the “new normal”—when public space is changing and communities must navigate uncertainty.

Source: Read Full Article