‘I saw a woman being told that her child had been killed. She crumpled to the floor emitting this most animal cry of anguish, the most disturbing sound you could possibly imagine.’

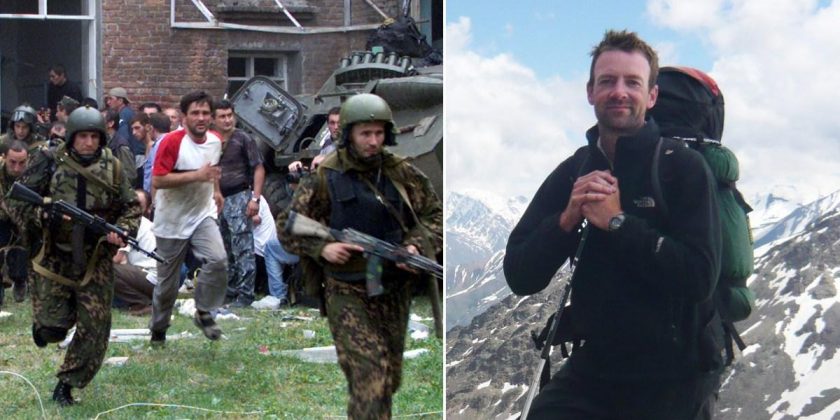

Those are the harrowing words of writer Tom Parfitt, who witnessed the horrors of the Beslan school siege while working as a Moscow correspondent.

It was September 1, 2004, the day Chechen rebels took 1,200 adults and children hostage at a primary school in Beslan, Russia. It was also the day Tom’s life changed forever.

‘That was an image that would come back to haunt me in a recurring nightmare for years afterwards. In the nightmare everything is the same as it was in reality. I only see her. I can’t do anything.’

Tom covered the hostage situation until September 3. 186 children and more than 144 adults were killed as the situation erupted in an explosion and bullets.

It also left more than 700 wounded. Tom also reported on the aftermath and was so affected by it he set out on a 1,000 mile walk to try and see the better side of Russia.

The ordeal still haunts Tom all these years later, leading him to write his newly-released book, High Caucasus, which follows his healing journey as he trekked the mammoth distance. While it’s not an attempt to whitewash the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Tom is also seeking to remind us that there are still good and kind people within its borders.

Recalling his memories of the siege, he told Metro.co.uk: ‘They had all been forced into this school into the gym and were being held hostage there. Later we found out the militants had rigged the whole place with explosives so it was an incredibly tense and emotional situation.

‘There was a terrible feeling of powerlessness of the dads who were there with their wives and children in the school just tearing their hair out saying “what can I do” and there’s nothing you can do. You just have to wait.’

On September 2, 26 hostages were released, but less than five hours later 20 male hostages were executed and dumped out the windows.

Tom says: ‘We found out that the hostages had been denied water, they were racked by thirst, it was very hot, the children had stripped off all their clothes because they were pouring with sweat.

‘They had nothing to eat, they weren’t allowed to go to the loo, some of them had soiled themselves.

‘One of the militants had his foot on a switch that could detonate the explosives at any moment, they were terrified and no-one thought they would get out of there alive.’

But the agonising choice one mother had to make sticks in Tom’s mind.

He said: ‘There was a woman who was in the school with an infant, of whom they were able to secure the release, and she also had a slightly older child.

‘The militants said to her “you can’t take them both out, you can either go with your infant or you can stay here with both of them”.

‘So she thought, I’ll save one, so she left with the younger child. But she described how she had to look at her five-year-old daughter and say goodbye.’

Very fortunately, the child survived and was reunited with their mother. Tom says he tries to ‘latch on to those moments of positivity’ to help ease the trauma.

‘I saw a man in shredded clothes just shivering in terror, lying on the ground’, he recalls when contemplating the siege’s aftermath.

‘I saw bodies of children lying under a sheet. One or two of them were so young that their feet were still plump and doe.

‘I went to the morgue and saw hundreds of child bodies wrapped in tin foil. The whole field turned into a cemetery outside.

‘Then I just couldn’t take it anymore I said to my editor “I have to go home”.

‘I went away for a while but I had this recurring nightmare and I was thinking about it an awful lot.

‘None of this compares to the terrible suffering of the people involved, theirs is obviously 1000 times worse, but nonetheless it’s distressing to see these things.’

The sheer amount of loss felt by the 35,000 strong population of Beslan became apparent when Tom made one particular phone call.

‘I rang someone to talk about their daughter. It was the mother of a girl who had been killed and I talked to her for several minutes explaining why I was calling, but it was only after a while that I realised I had gotten the wrong number,’ Tom says.

‘There were so many people in the town affected that you could call the wrong number and get someone else whose daughter was also killed.’

After leaving Beslan, Tom tried to ‘get on with reporting other stories’ but felt ‘nothing could match the emotional intensity and importance of what had happened in Beslan’.

‘It’s hard to leave it behind. That lasted for a long time. It wasn’t until three or four years later that I began to think “can I walk across the north Caucasus?”,’ adds Tom.

Tom got a grant from the Geographical Society to walk from the Black Sea to the Caspian, roughly 1,000 miles, and set out in spring 2008 before finishing that October.

He explains: ‘I was still having my nightmare and I thought it could be a way of diluting those bad memories and finding another more positive side to Russia.

‘Then I could also understand more about the roots of the violence in the region and think “were there some things in the background I didn’t understand?”‘

Tom spent months walking through high mountain passes and woodland under heavy rainfall. He stayed in shepherd’s huts or camped and got detained by Russian forces on several occasions believing he was a spy.

On one of the occasions Tom was arrested he says: ‘There was a good cop bad cop thing where I got passed between different agents who tried different things to try and force me into saying I was spying.

‘They held me overnight in a hotel with the interrogation set to continue the next day.

‘That was stressful and my stomach was churning thinking “oh my god what is going to happen here”.

‘Normally it’s just theatre but this time it was very intense and I thought they may use me to set an example.’

Ironically Tom believed at one point he would meet his end at the hooves of a wild boar. He says: ‘I met a wild boar and I startled it. It reared back on it’s legs and I thought right I’m done for now.

‘I just ran away in a ridiculous fashion and dove into a hollow, and then nothing happened and it trotted away with two little piglets. It was a bit humiliating.

‘That same night I heard a big beast in the forest around me but I realised it was the noise of my stubble rubbing against my sleeping bag.’

But despite all the ups and downs along the way, Tom said the 1,000 mile walk helped him to heal.

He says: ‘Walking itself has restorative power. It is a healing thing, just walking, the liquid rhythm of it, is something special.

‘I had seen the very violent bloody side of Russia but on the walk I saw this incredible beauty.

‘I saw amazing human resilience, I witnessed people doing heroic deeds, people outside enjoying the sunshine and mountains and all of those experiences, they didn’t overwhelm the bad things but they polluted them.

‘What I saw was people living and thriving on the stoniest of grounds. There are nations inside Russia who have suffered as much as the Ukrainians in their past.

‘There is another Russia, a different one to the dictatorial state. My walk in the Caucasus shows that there are wellsprings of human kindness from which another Russia will spring one day.

‘I don’t believe it should white wash what is happening in Ukraine but I do believe there is another Russia.

‘You look at people’s individual trauma who lost their children in Beslan and you think it would be great if they could be allowed to forget.

‘But we have to remember. I ended up thinking that for myself, for my own small story, I don’t want to forget about Beslan because in some way the restitution, it’s a way of restoring justice, is to remember.’

High Caucasus: A Mountain Quest in Russia’s Haunted Hinterland by Tom Parfitt, £18.99

Despite all the trauma Tom experienced this book is uplifting and hopeful.

Do you have a story to share?

Get in touch by emailing [email protected].

Source: Read Full Article