A study in pregnant women shows a higher percentage of detectable infections with clinical impact in primigravid women (first pregnancy) as compared to women with two or more pregnancies (multigravidae), especially in regions with high transmission of the disease. When transmission declines, parasite density in primigravid women also declines, contrary to what happens with multigravidae.

These findings suggest the existence of non-immunological factors in the control of infections. The results of the study, led by ISGlobal, a center supported by the “la Caixa” Foundation, and the CISM, have several public health implications, including the efficiency of diagnostic tools to detect malaria infections and therefore the ability to provide appropriate treatment.

The ability to detect malaria infections is highly dependent on parasite density. Infections with a very low density may escape commonly used diagnostic methods (microscopy or rapid antigen tests). Parasite density is thought to depend on host factors, and in particular the level of immunity against the parasite.

“Surprisingly, in areas where parasite transmission is low, and therefore where immunity is expected to be low, low-density infections prevail,” says Alfredo Mayor, researcher at ISGlobal and CISM, and coordinator of the study. “This suggests there is another factor affecting parasite density, which is independent of immunity,” he adds.

To better understand the relationship between transmission intensity, parasite density, and immunity, Mayor and his team conducted a prospective study over three years (from 2016 to 2019), in which they quantified P. falciparum infections with molecular methods (PCR), as well as antiparasitic antibodies in pregnant women attending their first antenatal visit.

In particular, they measured a type of protective antibody that is only generated after the first pregnancy, following placental infection. The 6,471 women who participated in the study lived in three regions of southern Mozambique with different intensities of disease transmission: Ilha Josina, with high to moderate transmission; Magude, where transmission went from moderate to low thanks to an elimination project; and Manhiça, where transmission has always been low.

“We analyzed the samples with the aim of testing the hypothesis that immunity acquired by pregnancy is the main factor controlling parasite densities in women who have already had more than one pregnancy, while other non-immune factors intervene in women who are pregnant for the first time and who lack such immunity,” Mayor explains.

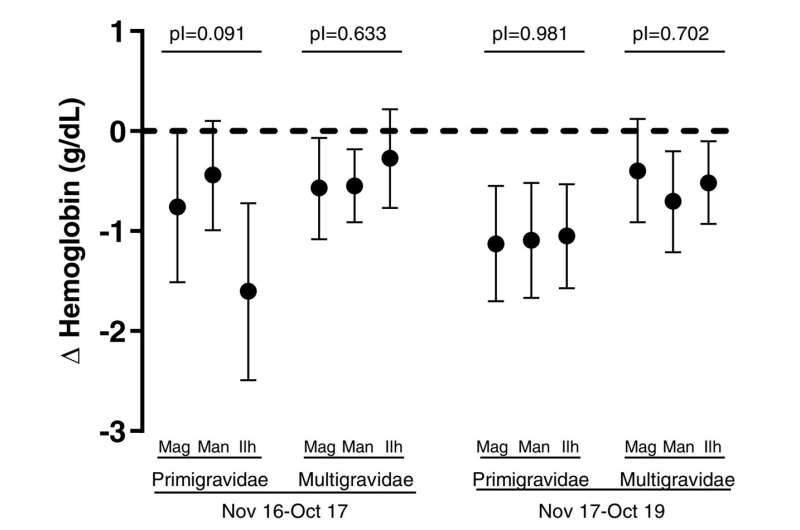

The results obtained confirm this hypothesis. The highest parasite densities (and therefore the easiest to detect) were in primigravid women in Ilha Josina. These infections, besides being detectable, were clinically relevant (the women had less hemoglobin in blood). As disease transmission in the area decreased over the three years, from high to moderate, parasite densities also decreased in primigravidae, even though antibody levels remained stable.

“This suggests that there are other factors, regardless of antibody levels, that determine parasite density in areas where transmission declines rapidly,” explains Gloria Matambisso, first author of the study. In contrast, in multigravid women (two or more pregnancies) the opposite was observed: parasite densities increased as transmission decreased. This is somewhat to be expected, since reductions in transmission imply less risk of infection and therefore less likelihood of acquiring immunity against the parasite.

Although further studies are needed to identify the “non-immunological” factors that regulate parasite density in primigravid women, the authors point out that these findings have important public health implications.

First, that the efficiency of current diagnostic tools to detect P. falciparum infections depends on the intensity of transmission and whether it is the first pregnancy or not.

Second, that infections may have a worse impact on multigravid women when transmission declines rapidly. “This study also highlights the value of monitoring malaria infections in pregnant women, as it allows us to detect geographical and temporal changes in the general population,” Mayor points out.

The research was published in BMC Medicine.

More information:

Glória Matambisso et al, Gravidity and malaria trends interact to modify P. falciparum densities and detectability in pregnancy: a 3-year prospective multi-site observational study, BMC Medicine (2022). DOI: 10.1186/s12916-022-02597-6

Journal information:

BMC Medicine

Source: Read Full Article