A well-known food fact of life in New Orleans: The natives live to eat, contrary to the more widely accepted notion that most people eat to live. Many of New Orleans’ culinary staples — red beans and rice, shrimp jambalaya, crawfish etouffee — are fan favorites thanks to copious amounts of hot sauce that amps up heat and spikes the flavor.

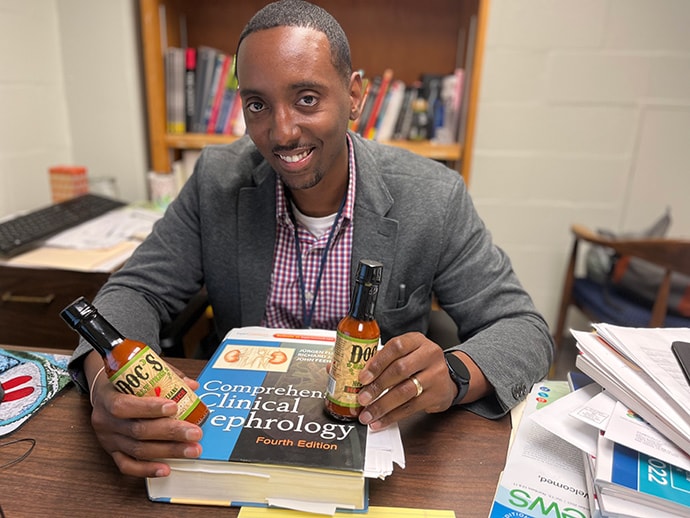

“New Orleans folks say they don’t pour hot sauce on their food, they put food in their hot sauce,” said nephrologist Adrian Baudy IV, MD, MBA, associate professor at Tulane University School of Medicine.

Baudy, the nephrology training director and medical director of the dialysis unit at Tulane, suspected that the ubiquitous hot sauces were exacerbating the kidney disease of his patients, and raising his father’s chronically high blood pressure. “Processed food in America is loaded with salt, especially condiments. The average American eats 3400 mg daily — and [this number] is likely much higher in poorer urban cities like New Orleans,” Baudy said.

Hot sauces aren’t the worst offenders when it comes to sodium — although some brands can have more than 100 mg of sodium per teaspoon — but overzealous use can be a problem, he said.

Knowing he was up against a cultural and culinary habit that his patients were having a hard time quitting, he decided to concoct his version, Doc’s Salt Free Hot Sauce, in hopes of convincing patients to try a salt-free dash or two of the spicy stuff.

Dr Baudy with his healthier version of a tasty condiment — Doc’s Salt Free Hot Sauce.

Inventing potent recipes seems to be in Baudy’s DNA. At age 6, he tinkered in his mom’s kitchen attempting to make his own root beer. Mixing a little root beer extract with Pepto-Bismol, he figured, would create a facsimile of a favorite soda. His mom’s puckered reaction when she took a sip was not the rave review he’d hoped for. But to him, it didn’t taste all that bad.

To this day, Baudy laughed, “I’ll try anything.”

From Clinical Experience to the Kitchen

Baudy, now 39, recognized that the amount of salt — and hot sauce, the condiment of choice — in his patients’ diets was unhealthy.

Determined to help them kick their salt habit, he began experimenting in the kitchen again, this time harvesting peppers from his garden and marinating them in white vinegar.

After numerous tweaks, his dad’s initial reviews ranged from “ohh, too hot,” to “ugh, too liquidy,” to “hmm, not hot enough.” Many iterations later, when his dad nodded approval and ordained a batch, Baudy knew he had a concoction that might approximate the punch delivered by conventional hot sauce.

His objective was to bring awareness to the dangers of high sodium intake, which the federal government was adamantly advising consumers to reduce. “Given the impact of excess sodium in our diet, no other dietary modification would have the health benefit or population reach of sodium restriction,” Baudy wrote on his LinkedIn page.

Most of his patients get the message from Baudy personally. Kenneth McMillan, 54, said he liked his food salty and spiked with plenty of hot sauce — a combination that drove his blood pressure to the 220/195 zone.

“Dr Baudy told me I had to back off the salt. My blood pressure was so high he said it was weighing down my kidneys,” McMillan told Medscape Medical News. Baudy’s sobering message: “Your kidneys are going to blow out.”

At a clinic appointment several years ago, Baudy handed McMillan a lifeline — a bottle of his hot sauce along with a sample of salt-free salad dressing he was beginning to develop.

“I’ll be honest, I didn’t much care for the salad dressing; I’m not much of an oil-and-vinegar kinda guy. But I loved the hot sauce,” McMillan said.

To preserve his kidneys, McMillan started prepping more healthy meals, using the salt-free sauce as a cornerstone. While those changes did not prevent him from requiring a kidney transplant a few months ago, he credits the sauce with helping him maintain a healthier blood pressure of 150/83.

Along the way to perfecting the salt-free hot sauce, Baudy’s entrepreneurial efforts hit many setbacks. Like the time he shipped the hot sauce to customers in packaging cushioned with bubble wrap and carefully marked “Fragile.”

Feedback came swiftly in the form of complaints that bottles arrived broken, splattering the contents on recipients who demanded Baudy reimburse them for dry cleaning bills.

Or the time the landlord of Baudy’s subleased self-storage unit skipped town owing months of rent to the property owner, who threatened to seize Baudy’s inventory as collateral.

As a youngster growing up in New Orleans, Baudy was a frequent visitor to hospitals where his aging great grandparents and grandparents were undergoing treatments for heart disease, kidney disease, high blood pressure, and stroke. He was struck by how they struggled to communicate with their doctors, whose time constraints provided only hurried sound bites in response to pressing questions. The doctors’ brief encounters with patients prompted Baudy’s first notion to become a physician, he said.

Following medical school at Wright State School of Medicine in Dayton, Ohio, Baudy circled back to New Orleans for residency in 2009. The city had been ravaged by Hurricane Katrina 4 years earlier, and Baudy was drawn to Tulane’s innovative ambitious “come back” campaign. ” ‘We’re going to rebuild’ was the prevailing attitude,” Baudy said, “and I was all in.”

Today, a father of three sons, 11, 9, and 7, and married to his college sweetheart, Jennifer, a social worker, Baudy has a hard time being idle. “If I get free time, I gotta do something,” he said.

Taking courses two nights a week from 2016 to 2019, he earned a business degree from Tulane. The effort paid off, he said, as the program’s emphasis on entrepreneurship equipped him with a keen appreciation of the value of networking and an opportunity to develop his salt-free hot sauce into a marketable commercial product.

For a year or two Baudy gave away bottles of the salt-free concoction he poured into 5 oz mason jars to patients who had heard of it by-word-of-mouth. But eventually nights cooking and bottling into the early morning wore him out and he knew it was time to find outlets for production and distribution.

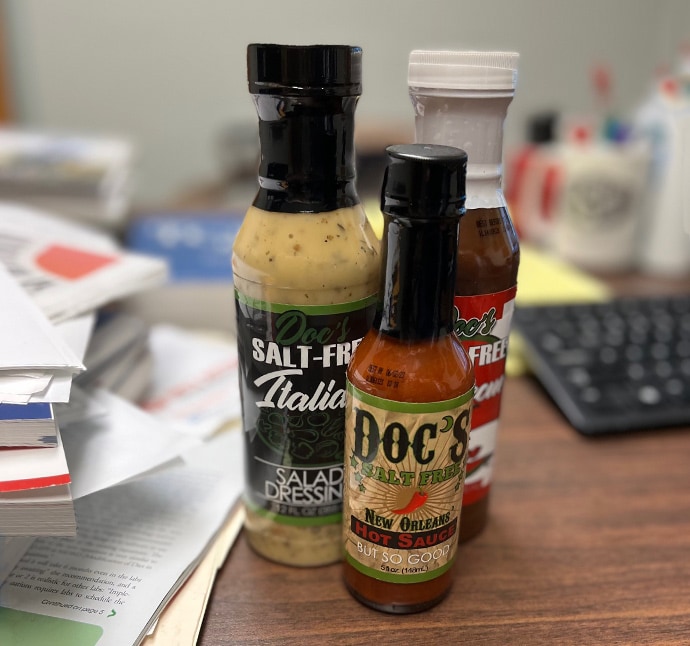

To streamline operations, he found a co-packer in North Carolina and signed on as a seller with Amazon. Baudy’s ingredients are simple: cayenne pepper, porcini mushroom powder, onion powder, garlic powder, lemon juice, a dash of brown sugar and beet powder to provide color.

He designed the label with an image of what he calls “New Orleansy stuff” — a crescent moon (a well-known symbol of the city) and five-pointed stars that grace the covers of the city’s water meters. Even with no marketing budget, sales have slowly and steadily increased. He attributes the increase to the pandemic years — from 2000 bottles a month 2 years ago to 4000 a month today — to consumers taking their health more seriously.

The retail price has remained at $3.99 for a 5 oz bottle, but shipping has increased the cost to $8.99. Baudy has poured whatever profit he makes into developing other salt-free products, including a new barbecue sauce and an Italian-style salad dressing. Up next is a honey mustard dip and salad dressing. But not every idea pans out. “We stopped the strawberry hot sauce; despite people loving it, there wasn’t enough demand,” he said.

Baudy said his motive has not been the money. “I just wanted to bring something into the world that solved a problem,” he said.

Serving Up Sauce, and Expertise

Colleagues often ask Baudy how he advises patients to control their sodium intake.

“Everyone swears they are on a low-sodium diet,” he told Medscape. “I start with a 48-hour diet history. It’s funny how many people had a McDonald’s breakfast that morning. And then [I] ask how often they eat out and want them to Google how much sodium is in the fast food item.

“They say, ‘Wow’, and then I set their limit. The general limit is 2300 mg in most patients, but I individualize it based on disease and guidelines for that particular disease,” Baudy said. He tracks sodium intake by monitoring a patient’s blood pressure and swelling. He allows patients a weekly “cheat day,” normally for football games on Saturday or Sunday, but not both.

Dr Baudy has poured the profits from Doc’s Salt Free Hot Sauce into developing other salt-free products like barbecue sauce and an Italian-style salad dressing.

His patients are motivated by positive feedback. They typically respond “very well when they see symptoms improving (with the reduction of their blood pressure and swelling.) I use improvements to reinforce their behavior,” he said, estimating that the strategy works for about 80% of his patients.

“I spend time simplifying things as much as possible and avoid using medical jargon. I draw pictures and use analogies — like a car with two flat tires to illustrate a patient’s diseased kidneys,” he said, adding that he or his nurse will follow up by phone to make sure patients understood what was discussed.

Baudy’s boss, Lee H. Hamm, III, MD, senior vice president and dean of Tulane University School of Medicine, has not sampled the hot sauce, but said Baudy has helped improve healthcare beyond the nephrology clinic.

“We all know that kidney disease disproportionately strikes African Americans who have hypertension,” Hamm said. “For Dr Baudy to come up with [a salt-free hot sauce] is ingenious. It meets a combination of being mission-driven and solution-driven. He is an extraordinary type of physician that makes you enthusiastic about the future of medicine.”

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn

Source: Read Full Article